Judy Garland’s greatest performance is in the 1954 version of “A Star Is Born,” but her greatest movie is “The Clock” (streaming on multiple platforms, including the Criterion Channel), from 1945, which was directed by her soon-to-be husband, Vincente Minnelli. It’s the film in which Minnelli first unleashed the full force of his artistry—and he did so thanks to Garland’s own dramatic power. Garland was born on June 10, 1922, and “The Clock,” shot in late 1944, when Garland was twenty-two, is the first movie in which she starred but didn’t sing. It’s strictly a romantic drama, and its drama is rooted in the overriding story of the historical moment, the Second World War. The greatness of “The Clock” extends into many dimensions: as a movie of life on the home front and in military service alike; as a New York City movie; and as one of the most rapturous, tender, and, indeed, erotic romances released by a classic-era Hollywood studio.

Garland’s acumen and clout are at the movie’s very basis. She had lobbied her bosses at M-G-M for a dramatic, nonsinging role, and “The Clock” went into production under the direction of Fred Zinnemann, an Austrian Jewish émigré who was something of a specialist in social-realistic dramas. Garland was unhappy with the progress of the shoot and persuaded the film’s producer, Arthur Freed (the studio’s main musicals supervisor as well as a prominent lyricist, whose credits include the song “Singin’ in the Rain”), to replace Zinnemann with Minnelli. She had already worked with Minnelli for the musical “Meet Me in St. Louis,” and he was also her romantic partner. (They married in June, 1945.) The choice proved inspired. Minnelli and Garland share an emotional and artistic connection that elicited her freely expressive performance and his distinctive artistry. Though he was an exquisite cinematic stylist, his decorative methods aim at a kind of realism all his own. “The Clock” offers an unbroken skein of poignant, tangy, and sensitive performances in a display of directorial virtuosity that was rare in Hollywood or, for that matter, anywhere. Far from being a mere exercise in visual style, Minnelli’s direction incarnates a wide-spanning philosophical world view and an ardent emotional intimacy.

Garland plays Alice Maybery, a secretary who has been living in New York for three years. One Sunday afternoon, as she passes through Penn Station—a grand, cathedral-like hall that was shuttered in 1963 and then demolished—she trips over the inadvertently outstretched leg of Corporal Joe Allen (Robert Walker), who has just begun a forty-eight-hour furlough, after which he’ll ship out for overseas duty. Joe, who’s from a small town in Indiana, has never set foot in New York before, and overwhelmed by his first glimpse of the city, asks Alice to show him around. What begins, for her, as a grudging and uneasy duty quickly blossoms into a warm mutual connection and a breathless romance.

It takes a city to bring a pair of young lovers together. The movie is built around a Rube Goldberg-esque mechanism of fortuitous connections involving a series of coincidental meetings with strangers who play large or small roles in the life of the couple as the bonds of romance tighten and they rush toward a wartime marriage. Reportedly, Minnelli himself changed the script so that it opens on a teeming array of happenstance characters, strangers whom Joe encounters, from one to another, before he stumbles upon Alice (or vice versa): a shoemaker closing up shop, a conductor on the top of a double-decker bus, children in the park and the museum, waiters in restaurants or the many passersby who randomly intrude on personal moments and drive the couple into self-conscious silences, a milkman who gives the couple a lift on a joyful yet serious nighttime adventure, the chain of officials whose daily rounds and exceptional efforts are essential to the couple’s ultimate union.

In a directorial career that ran from 1942 to 1976, Minnelli was the poet of institutions, a forerunner in fiction of Frederick Wiseman, dramatizing the inner workings of theatres, schools, families, a mental hospital, the American West, and Hollywood itself. In “The Clock,” Minnelli takes on the majestic and mighty institution of the city, and unfolds its inner workings with a sense of wonder. The delicate interconnections of seeming coincidences, the summed-up meaning of bare practicalities, veers toward the metaphysical and heightens each banal moment with an air of destiny. (Even the timepiece of the title is both an actual New York landmark—the one in the Hotel Astor (torn down in 1967), where Alice tells Joe to meet her that night—and a metaphorical one, devouring the brief and precious time before Joe’s departure.) The movie’s urban vision is all the more striking for its essential artifice: it was made in the studio, on colossal sets, involving rear-screen projections and enormous hyperrealistic paintings that served as backdrops. Minnelli brings the station, the hotel, the park, the streets, churches, apartments, and even the corridors and offices of City Hall and the warrens of downtown business-district offices to cinematic life with a vividness that’s synergetic with the passions of the people who pass through them and depend on them.

Minnelli is most celebrated for his musicals, though I consider his nonmusical dramas and comedies to be his greatest achievements. In “The Clock” he lends the drama a musical-like choreographic splendor, on a grand scale, as in the roving camera amid the turmoil of Penn Station, and in an elaborate subway scene that’s all the more powerful for its blend of quasi-documentary accuracy and the hectic terror of separation and loss in the surging tide of the crowd. The near-miss irony of these coincidences lends the film a frantic, tragicomic verve. Several of the movie’s most memorable moments belong to extras, such as a pair of sanitation men who, by way of posture only, vividly convey—thanks to the canny precision of the overhead framing—their astonishment at seeing a uniformed soldier and a woman in evening garb delivering milk before sunrise. Minnelli fills the movie with such high-angle shots, peering down at Alice and Joe, whether panoramically or in extreme closeup, as if rooting them in the city’s streets and crowds. During a scene of the couple sharing a quiet but mighty outpouring of spiritual devotion in the pew of a church, Minnelli deploys a sexton, silently passing between the camera and the couple, to blot out Garland and Walker at a moment of sanctified love that exceeds the possibility of it being acted out and, so, is thereby merely suggested to viewers’ imagination.

But, of course, the center of the movie, its very engine, is Garland. She invests Alice with a blend of determination and wariness, weary solitude and pent-up energy. She builds the role with gestures that are choreographically etched and vocal inflections that, with their rhythm and pitch and emphases and space and silence of music, are themselves a kind of singing. The movie is filled with her infinitesimal yet mighty touches, as in the combination of gesture and lilt when she flaunts, to her roommate Helen (Ruth Brady), a gift from Joe. And Minnelli is clearly aware of the force of her performance, creating long takes that serve as a sort of proscenium as well as urgent closeups that burst with her tremulous power.

Above all, “The Clock” is a movie of intimacy, nowhere more than in a sequence that I consider one of the greatest ever filmed. It’s a nighttime scene in a park, where Alice and Joe first acknowledge, to each other and, seemingly, to themselves, that they’re in love. Minnelli crafts an extended and complex series of images of furious stillness and graceful, nearly balletic maneuvering until the lovers converge and kiss, under the glow of streetlights, in a matched series of some of the most ecstatic closeups I’ve ever seen. At a moment of most fervent passion, Garland’s right eyebrow twitches, and that tremor—magnified by Minnelli’s rapt scrutiny—resounds visually like a crashing wave of uncontrollable desire. “The Clock” feels like the closest thing to an erotic documentary that Hollywood could offer at the time of the Hays Code; the fact that it was released uncontested suggests the insignificance and feebleness of the code, and, even more, of directors who took its dictates as constraints on their art.

As Joe, Walker has a nearly campy intensity that captures the inexpressible fear of war’s consequences at the root of the role—and that the script itself, by Robert Nathan and Joseph Schrank, catches. Joe has an irrepressible urge to talk; he tells Alice about his dreams and ambitions, his life back home in Indiana, his boyhood reminiscences. It’s as if he were uploading his memory to a stranger for safekeeping, in case he doesn’t come back. The hint of the legacy of wartime marriages—of children to carry on the lineage of men who don’t survive battle, of fatherless children and young widows—haunts the action from the very start. “The Clock” is a movie of the social construction of private life, of love and loss, of sex and death—of ineffable beauty and its inexorable connection to horror. Its vision of the cinema as a living incarnation of a crucial historical moment is, itself, historic.

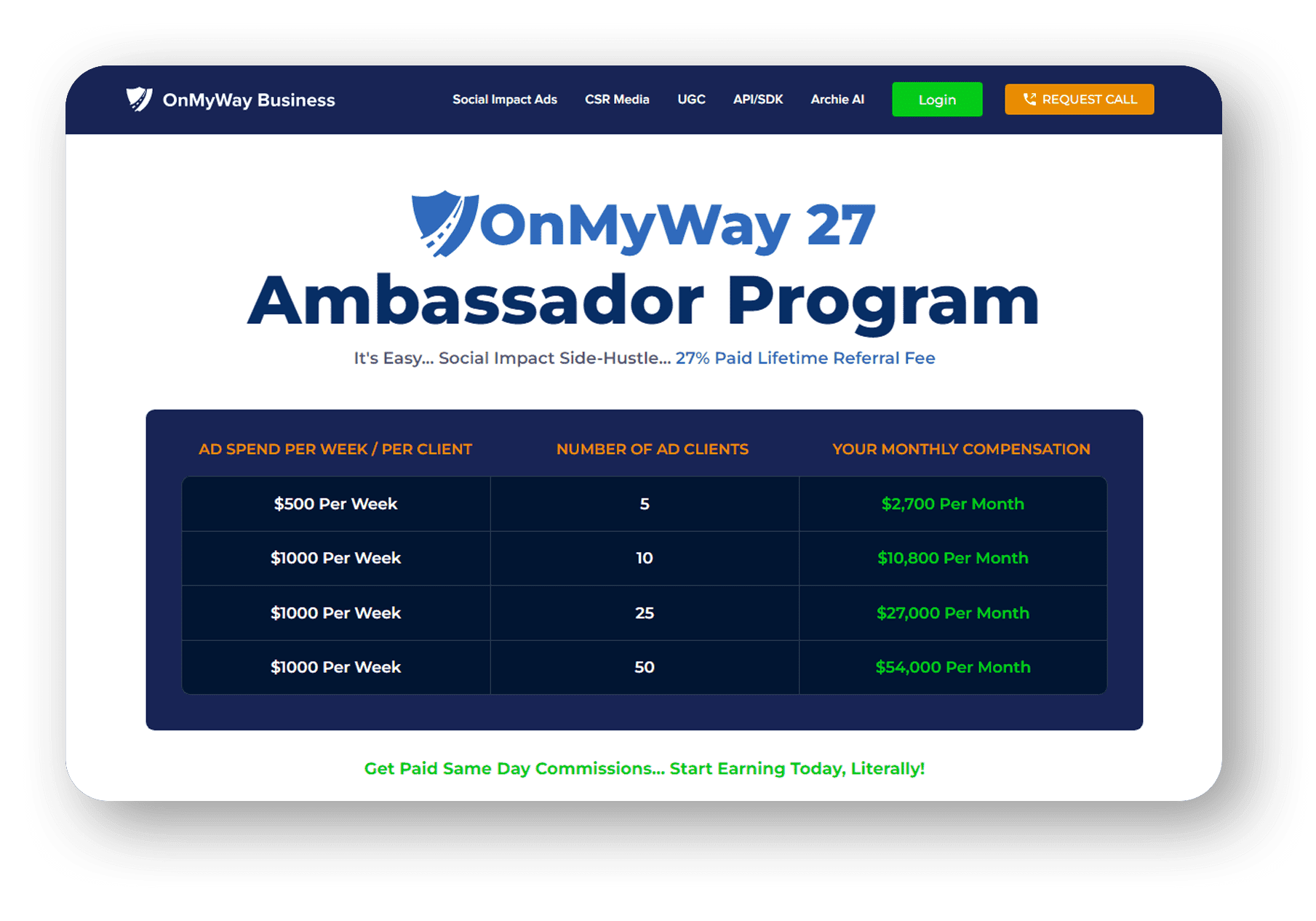

OVERVIEW

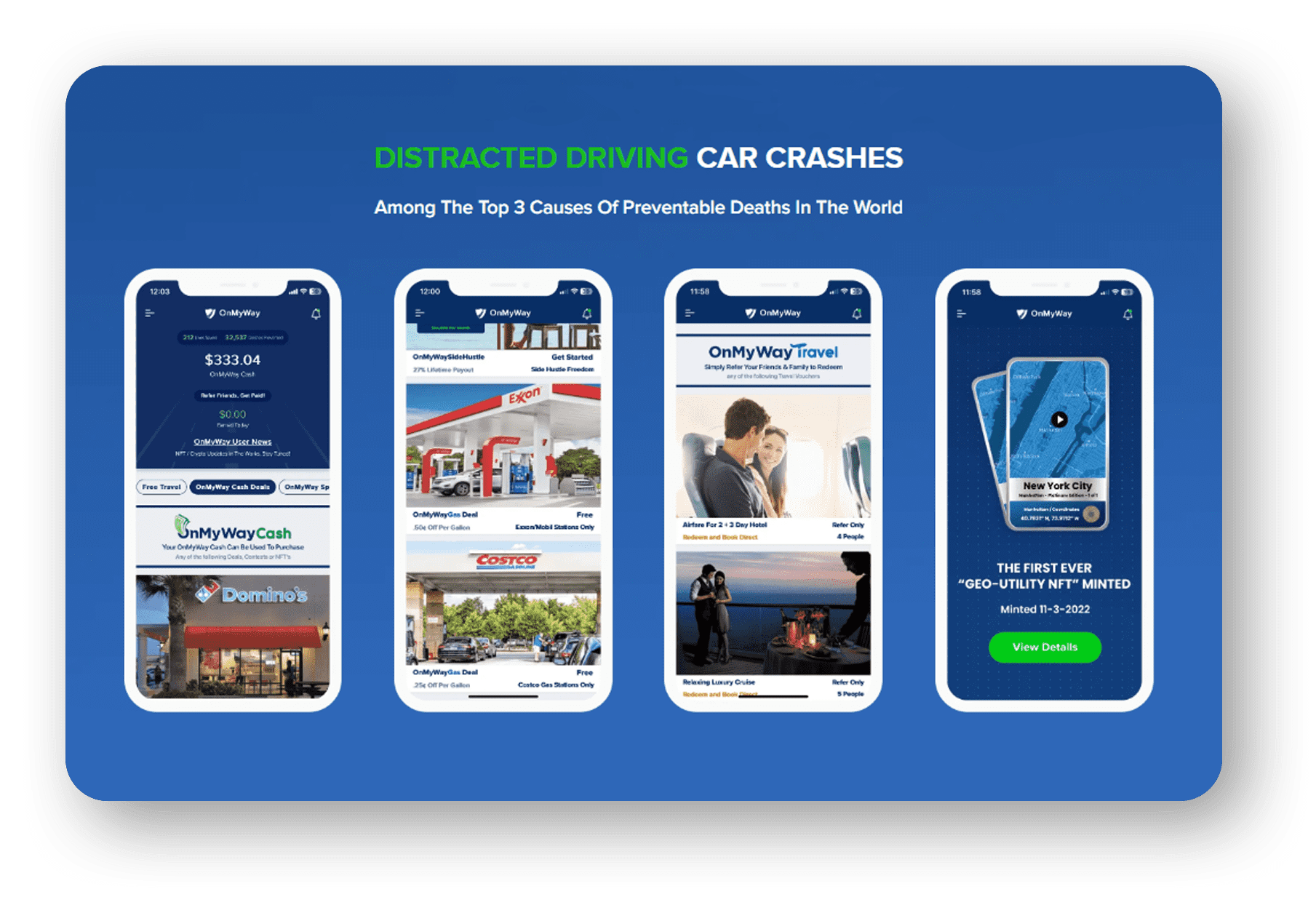

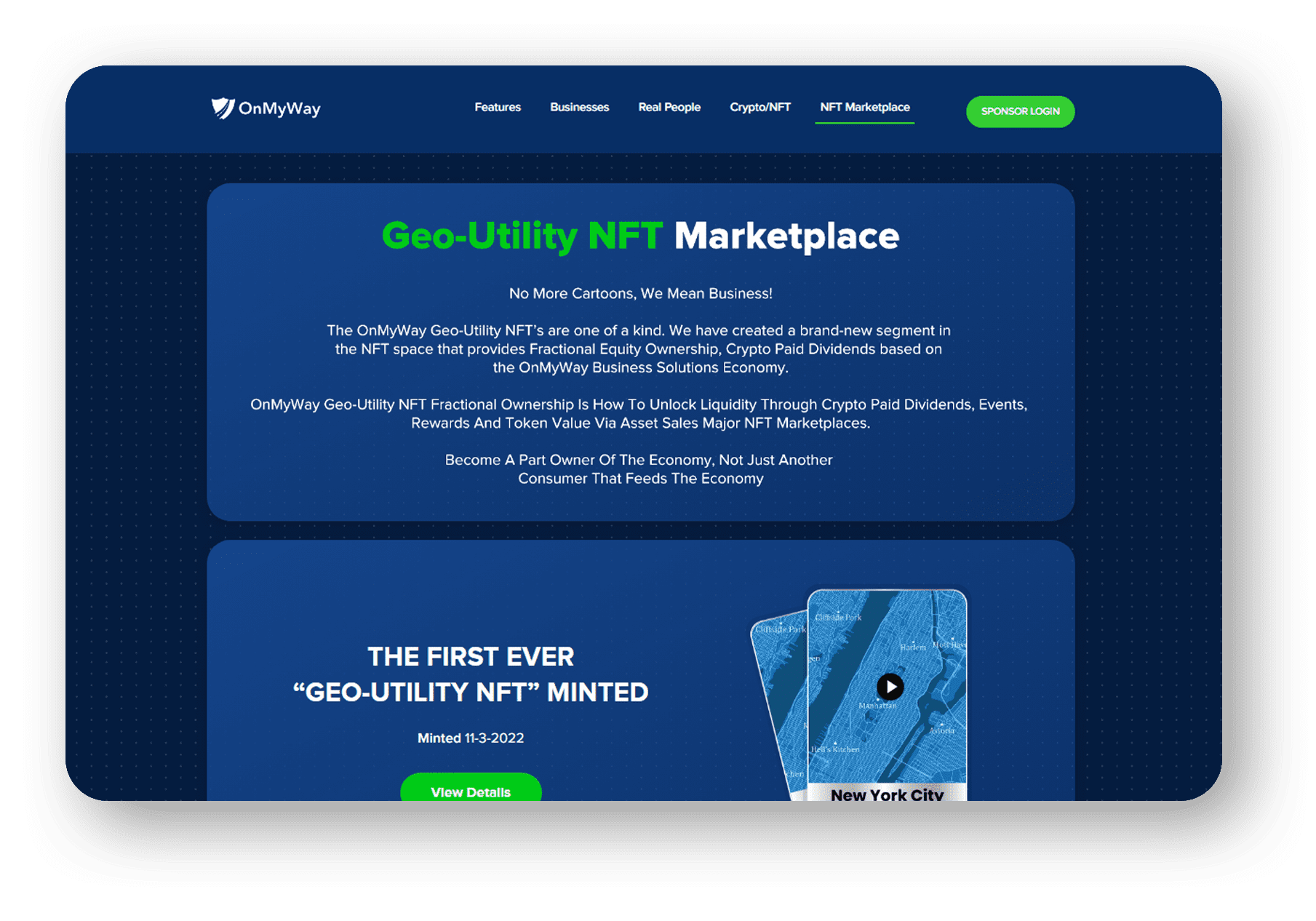

OnMyWay Is The #1 Distracted Driving Mobile App In The Nation!

OnMyWay, based in Charleston, SC, The Only Mobile App That Pays its Users Not to Text and Drive.

The #1 cause of death among young adults ages 16-27 is Car Accidents, with the majority related to Distracted Driving.

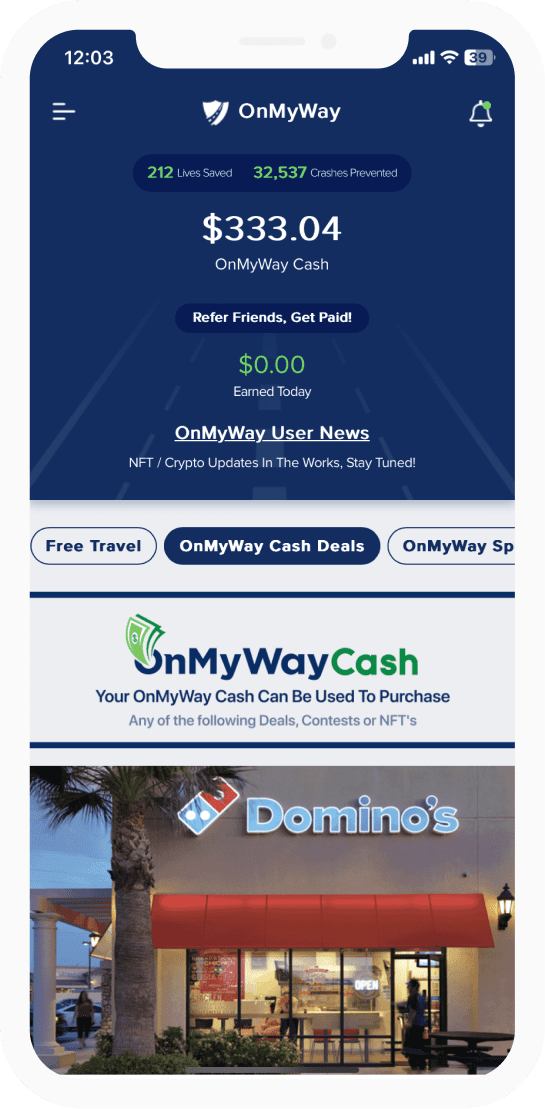

OnMyWay’s mission is to reverse this epidemic through positive rewards. Users get paid for every mile they do not text and drive and can refer their friends to get compensated for them as well.

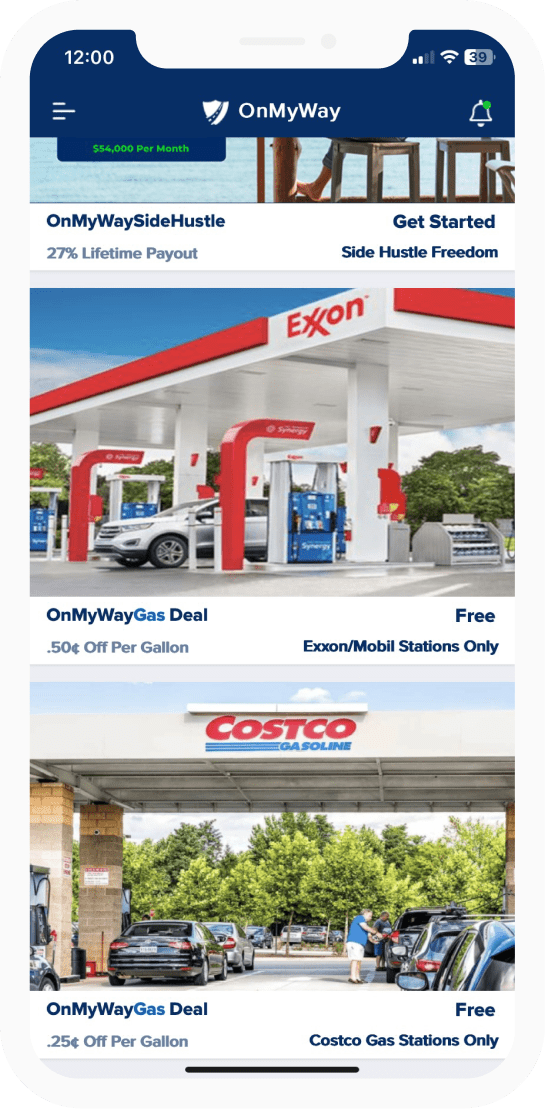

The money earned can then be used for Cash Cards, Gift Cards, Travel Deals and Much, Much More….

The company also makes it a point to let users know that OnMyWay does NOT sell users data and only tracks them for purposes of providing a better experience while using the app.

The OnMyWay app is free to download and is currently available on both the App Store for iPhones and Google Play for Android @ OnMyWay; Drive Safe, Get Paid.

Download App Now – https://r.onmyway.com

Sponsors and advertisers can contact the company directly through their website @ www.onmyway.com.